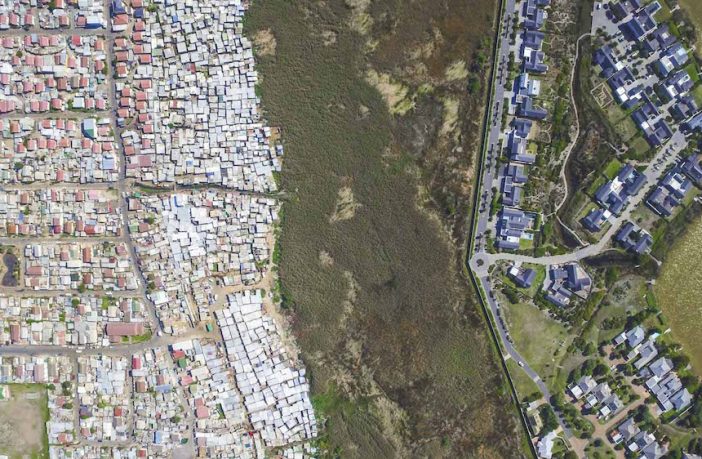

From the window of an airplane it’s all too plain that apartheid has been deeply written into the South African landscape. Even the smallest town appears as two distinct towns. One features a spacious grid of tree-lined streets and comfortable houses surrounded by lawns. The other, its shriveled twin, some distance away but connected by a well-traveled road, consists of a much tighter grid of dirt roads lined with shacks. Trees are a rarity, lawns non-existent. This doubling pattern appears no matter the size of the population: here, the white town; over there, the black township. — Lisa Findley, “Red & Gold: A Tale of Two Apartheid Museums.”

There are few systems of government that relied so heavily upon the delineations of space than the Apartheid government of South Africa (1948-1994). Aggressively wielding theories of Modernism and racial superiority, South Africa’s urban planners didn’t just enforce Apartheid, they embedded it into every city – making it a daily, degrading experience for South Africa’s marginalized citizens.

When Nelson Mandela and his party, the African National Congress, were democratically elected to power in 1994, they recognized that one of the most important ways of diminishing Apartheid’s legacy would be spatial: to integrate the white towns and the black townships, and revive those “shriveled twin[s].”

As we remember Mandela – undoubtedly the most important man in South Africa’s history – and ponder his legacy, we must also consider his spatial legacy. It is in the physical, spatial dimensions of South Africa’s towns and cities that we can truly see Apartheid’s endurance, and consider: to what extent have Mandela’s words of reconciliation and righteous integration, truly been given form?

Apartheid: A Spatial Overview

Every society produces monumental structures that commemorate and encapsulate its ideals; South Africa under Apartheid is no exception. As Lisa Findley and Liz Ogbu point out in their article “From Township to Town,” the designs of both Pretoria’s elaborate Union Building, the official seat of government, and the Voortrekker Monument, which memorializes the struggle of Afrikaans “pioneers”, for example, both validated and glorified the white minority.

But there is no greater monument to Apartheid than South African cities themselves.

The tradition of “apartness” began far before the system of Apartheid institutionalized and legitimized it; Apartheid just gave government officials the mandate they needed to purposely shape South African cities in a way that would benefit the white minority and mollify the black majority. (Although, of course, they never explicitly put it that way themselves. In 1950, Minister of the Interior, Dr. T. E. Tonges, justified the separation of the races in near medical terms: “Points of contact invariably produce friction and friction generates heat and may lead to a conflagration. It is our duty therefore to reduce these points of contact to the absolute minimum which public opinion is prepared to accept.”)

Thus, the goal, first and foremost, was to put blacks (via forceable removal or through the strict enforcement of “Pass” laws) in their own residential areas, or townships. These townships, often located as far from the town’s central business district (CBD) as possible, were then maintained separate via the use of natural and man-made barriers, such as railroads, roads, or open-space corridors (no-man’s-lands).

However, the “why” of separation still did not prescribe the “how” of its design. For that, Apartheidplanners turned to Modernism.

Apartheid: The Modernist Experiment

Inspired by writings like Le Corbusier’s 1922 Ville Contemporaine, which outlined the concept of housing for temporary labor, as well as Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities, Apartheid planners relied heavily upon existing Modernist models of suburbia. According to author David Kay, they believed that by using these Modernist principles, they could actually mold the native population in their image:

“…‘all reference to older modes of life, to history, to the sedimented place of memory, and to sociability had been eliminated’. This was the Apartheid state’s attempt to mold and reform the African society into a more modern, orderly underclass in spaces that were sterilized of all remnants of older African cultures and beliefs.”

Of course, this “moral” impetus had very little bearing in the physical result. While the white towns were designed as perfect Garden Cities, reaping the spacious, leafy benefits of suburbia, the black townships bore all its downfalls. Instead of suburban homes with spacious backyards, blacks were given small, identical “matchstick houses.” And, thanks to their physical location and an insufficient public transportation system, black residents were almost always hours away from the city center (where, of course, the only jobs/businesses were).

And this is why Apartheid, “one of the most inefficient and distorted” systems of sprawl ever designed, continues to affect black communities today. Although many middle-class blacks moved to formerly all-white suburbs – in fact this was the biggest population shift post-apartheid – most township residents did not.

To this day, townships, although vibrant communities in and of themselves, lack the commercial diversity of urban centers .Annemarie Loots, in “Soweto Integrated Spatial Framework,” notes that in the township of Soweto, which occupies only 10% of metropolitan Johannesburg but contains about 40% of its population, 70% of employed residents commute outside the township; only 26% of retail purchases are made in the township itself.

Occupying & Unraveling Apartheid

It should come as little surprise then, that as the anti-apartheid movement intensified, black citizens began to claim the space denied them.

In the 1960s, the early days of resistance, the ANC focused on sabotaging potent, built symbols of Afrikaans domination, such as government buildings and civic centers. However, over time, the resistance took the form of occupation as black South Africans began to form huge informal settlements on the empty land surrounding major urban areas. By the mid-1980s, thousands of blacks were in “white-only” areas, and the Apartheid government could not enforce its policy of separation. In 1986 the Pass Laws were abandoned, and, in 1991, the Group Areas Act (making legal the separation of blacks and whites) was as well.

And so, when President Nelson Mandela was democratically elected in 1994, he and the ANC attempted to right the wrongs that Apartheid had wrought.

First on the agenda: providing housing as a human right to every South African. Thus, the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP), purportedly aimed at promoting social integration and economic growth, was firstly tasked with building houses – lots of houses. About 350,000 a year.

Unfortunately, the need for cheap land on which to build these homes resulted in the construction of neighborhoods far from the city center, without the sufficient business or transportation infrastructures to support them. Although the government claimed that its efforts would turn “land development and land-use into integrated, ‘compact towns and cities’ […to] correct historical fragmentation and […] locate disadvantaged citizens closer to social and economic opportunities,” the result only exacerbated pre-existing, unequal sprawl.

Despite its good intentions and sound urban strategy, the post-Apartheid government lacked the cunning, the bravado of its Modernist predecessors, who had wielded design as their all-encompassing enforcer. Indeed, Apartheid remains so deeply gouged into the built fabric of South Africa’s cities that – even today – upturning it has proven no easy task.

Case in point: the 2010 World Cup.

A Tale of Two Stadia

The over-riding, iconic image of the 2010 World Cup, South Africa’s most recent moment in the spotlight, may well be the aerial shot of its brand-new Green Point stadium, with its stunning seaside location and privileged views of Table Mountain. However, few know the story behind its selection, nor the significance of this choice for the country.

Before Green Point was chosen to be South Africa’s iconic stadium, another had been slated for the honor: Athlone, situated in the historically-coloured, working-class neighborhood of the same name. City officials hoped that the World Cup would kick-start some well-needed development in the area, as well as in the abutting, impoverished township of Khayelitsha and the informal settlements along the nearby N2 freeway. In a letter to FIFA, one official wrote:

“The province and the City of Cape Town have always felt that the development of a dedicated football stadium in Athlone will leave a lasting legacy for generations to come. In addition, the building of the stadium will allow us to leverage much needed transport and other socio-economic developments in the surrounding area … We are expressing a strong preference in this regard.”

Gert Bam, the city’s director of sport and recreation, felt similarly: “Why we chose Athlone Stadium [was]not just because of football and that, but it would turn the city around, it [would]impact on this tale of two cities.”

Unfortunately, there was no denying that Athlone lacked tourist-appeal; as one blogger put it: “Athlone is surrounded by open fields, factories and housing projects. And a fair bit of barbed wire. I don’t quite see the tourists flocking there for an 8.30pm kick-off.” As time wore on, FIFA pressured city officials to consider building a stadium in the largely middle-upper class, white neighborhood close to the attractive V&A Waterfront. Green Point Stadium, FIFA suggested, would attract visitors and establish Cape Town as a world-class destination for major events, tourism, and investment.

We know which face South Africa chose to show the world.

So, to return to my original question: to what extent have Mandela’s words of reconciliation and righteous integration truly been given form?

Rising from the Ashes

In 1997, South Africa’s Department of Public Works held a competition to design the first major post-apartheid government structure – the new Constitutional Court Building. When the winner was announced, Mandela spoke these words:

“The Constitutional Court building will stand as a beacon of light, a symbol of hope and celebration. Transforming a notorious icon of repression into its opposite, it will ease the memories of suffering inflicted in the dark corners, cells and corridors of the Old Fort Prison. Rising from the ashes of that ghastly era, it will shine forth as a pledge for all time that South Africa will never return to that abyss. It will stand as an affirmation that South Africa is indeed a better place for all.”

The World Cup, which Mandela enthusiastically supported, was supposed to be an instance in which the city’s time, attention, and resources went towards re-designing the city to right Apartheid’s wrongs. Like the Constitutional Court building, the main stadium could have been a potent symbol, emerging from the remnants of Apartheid, rising from the ashes. But rather than a monument celebrating a nation overcoming its past, South Africa received a monument to the status quo.

Until Mandela’s words, floating in the ether, find themselves touching ground, coaxing a new shape out of South Africa’s cities and urging new, meaningful icons to grow, the reality will never live up to the rhetoric. Only then, when South Africa truly is “a better place for all,” will Mandela’s legacy be fulfilled.

Author: Vanessa Quirk

At the time this articile was published, Vanessa Quirk was the manager of editorial content at ArchDaily, where she wrote about architecture, design, and urban planning.

This article was first published in Arch Daily back in 2013 and is republished with permission.