Opinion

- Hydropower is an underutilised resource in Africa, which accounts for about 10% of the global hydropower potential. Tiaan Hendriks, Head of Energy Design at SEM Solutions explores small and micro hydropower generation as an option for South Africa.

People are always expecting the power to go out in South Africa due to rolling blackouts. Every time it happens, the possibilities of alternative power generation are discussed, usually with a focus on wind and solar power.

What about water?

Africa has vast resources and the potential for hydropower is one of them. About 10% of the global hydropower potential is located on the African continent with the majority of that in sub-Saharan Africa. So far only 4 to 7% of this potential has been developed.[1]

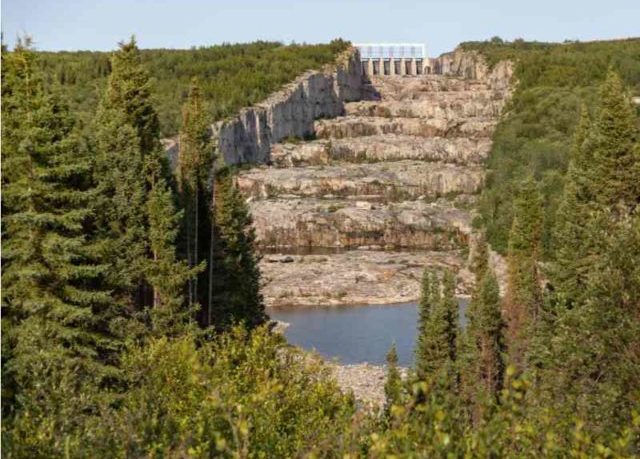

Water is usually considered for large installations, but small and micro hydropower could be an option for South Africa. It has worked here before. Micro hydropower generation has a history in South Africa and could potentially make a significant difference in the provision of electricity – especially in rural areas.

While there is no internationally agreed upon definition for the different sizes of hydropower, a generic distinction between ‘large’ and ‘micro’ hydropower is that micro-hydro usually refers to installations up to 10MW of installed capacity.[2]

For the last couple of decades, there has been advancement in the development of hydropower generation in South Africa.

There is the Neusberg Hydro Power Station near Kakamas in the Northern Cape, a new grid-connected micro hydropower station commissioned in the Sol Plaatje municipality in the Free State and a few other stations at varying stages of development.

Eskom operates four large stations (42MW Colley Wobbles, 360MW Gariep, 11MW Second Falls and 240MW Vanderkloof) and two micro hydropower stations (6MW First Falls and 1.6MW Ncora).

The Thaba Chweu local municipality owns a grid-connected station (2.6MW Lydenburg), while the private sector owns four stations connected to the national grid (300kW Clanwilliam, 2MW Freidenheim, 4MW Merino and the previously mentioned 3MW Sol Plaatje).

KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape also have a number of mini and micro hydropower systems that primarily supply individual farms only, without providing electricity to neighbouring communities.

The City of Cape Town operates hydropower turbines at four of its water treatment plants (700kW Blackheath, 1.475MW Faure, 340kW Steenbras and 260kW Wemmershoek). eThekwini is developing six sites, Rand Water another four sites at its infrastructure and Bloem Water a micro system to power its offices.

A 15kW pilot system was also installed at the Pierre van Ryneveld reservoir in Pretoria as part of a University of Pretoria research project[3].

Micro hydropower could play a pivotable role in remote areas to provide access to electricity in stand-alone isolated mini-grids or as distributed generation in national grids. Various national governments and donors have also recognised the potential role of micro hydropower in establishing access to electricity and eradicating energy poverty.[4]

Micro hydropower is a proven and mature technology with a track record. It also fulfilled a key role in earlier efforts to supply electricity in Southern Africa. Unfortunately, interest in micro hydropower waned when national grids offered cheap and reliable electricity.

A good example is the gold mines at Pilgrims’ Rest that were powered by two 6kW hydro turbines – as early as 1892. A 45kW turbine was added two years later to support those turbines to power the first electrical railway in 1894. Various church mission stations in Africa also used micro hydropower installations.[5]

While people forgot about micro hydropower when the national grid promised cheaper and more reliable power, the price and the fact that our electricity supply has become unreliable, indicates that communities in South Africa could consider generating their own power and they could be done with micro hydropower.

Micro hydropower in South Africa consists of two main parallel tracks. The first is IPP-developed grid-connected projects feeding into the national electricity system and the second is micro-scale systems for private use.

No support is available for isolated systems for rural electrification purposes at the moment, but government is currently reviewing its rural electrification strategy. In addition, the future of grid-tied systems is closely linked to government’s policy on renewable energy development.[6]

Challenges of hydropower in South Africa

To be realistic, there are challenges to using micro hydropower in South Africa. These challenges are:

- Policy and regulatory framework are unclear or non-existent with little clarity on issues such as access to water and water infrastructure and payments for water.

- Financing is a challenge, because hydropower developments have high up-front costs and low O&M costs, with most new developments on the continent relying on donor financing.

- A lack of capacity to plan, build and operate hydropower plants at political, government and regulatory entities.

- Data on hydro resources are limited.

- Policy and regulatory framework are unclear or non-existent to govern the development of micro hydropower.[7]

However, research has shown that twice the installed capacity of the present installed hydropower capacity below 10MW can be developed in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu Natal and Mpumalanga.[8]

Site examples would include places where dam water is released into bulk water supply lines; water treatment works where the inlet water source pipeline can be tapped; water reservoir inlets where pressure-reducing stations are used; water distribution networks and at treated effluent discharge points.[9]

Important factors that should be considered for a micro hydropower project are to determine project costs and electricity generation potential are the head, flow, penstock (pipeline) length and electricity transmission line length.[10]

Now for the benefits

However, now that we have discussed the barriers, let us remind ourselves of the benefits of micro-scale hydropower:

- It is considered a renewable resource;

- It is installed within existing man-made infrastructure and only a basic environmental assessment is required and no water licencing is required;

- In the case of “own use” generation, no generation licence is required from NERSA;

- Project payback times are relatively short, because little civil works are required and operation and maintenance costs are low;

- If hydro turbines are installed in parallel to existing pressure control valves, it can extend the operational life of the valves;

- The technology is efficient and durable for up to 20 years.[11]

The cost of a micro hydropower project is made up of civil works, mechanical and electrical components and electrical components such as grid connection and grid infrastructure.[12]

Case studies were done on micro hydropower projects at South African municipalities, in Cape Town, the eThekwini metropolitan municipality, KwaMadiba, Mhlontlo municipality and the Boegoeberg !Kheis municipality.

The challenges identified with these municipal projects were that each project had numerous stakeholders and entities, which introduces challenges in communication, approvals and time schedules. It was therefore clear that stakeholders need to agree on clear channels of communication at project inception.

The site terrain posed construction as well as access problems and getting approval from stakeholders and entities slowed the projects down. Importing products not available in South Africa was also high.

While implementation was quite straightforward, legislative procedures and bylaws challenged micro-scale project feasibility. The prevention of theft and possible injuries to children swimming in the canal sections were also major challenges.[13]

Although these challenges could be prohibitive, studies have demonstrated that South Africa has good potential for micro and even mini-hydro systems[14].

Micro-hydro systems can provide a reliable and continuous supply of electricity cheaper than wind or solar, with the added advantage that these systems are not affected by short term variations in weather. Innovation and increasing demand are bringing prices down, making micro-hydro systems an economically viable source of electricity.[15]

A key part of the Agenda for Sustainable Development is achieving universal access to electricity by 2030, because electricity is required for almost all parts of a modern economy, from cooling vaccines to irrigation pumping, from manufacturing to running a business. Micro-hydro power can help South Africa achieve this goal. It is time to start breaking down the barriers to micro-hydro power and get our regulatory environment and financing on track to use this environmentally-friendly way of generating power.

Author: Tiaan Hendriks

About the author

Tiaan Hendriks has a Masters in Mechanical Engineering in Renewable and Sustainable Energy from Stellenbosch University.

This article was originally published on ESI Africa and is republished with permission with minor editorial changes.

Disclaimer: The articles expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Green Building Africa or ESI Africa, our staff or our advertisers. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part Green Building Africa concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities.

Water is one of the central themes at: